In this article, I will present and explain a map of the vowel system specifically created to guide the general English language learner. The map is designed with three main aims in mind:

- To provide useful insights for the learner.

- To support memorable and effective classroom activities.

- To be relevant in an international context by being flexible enough to deal with accent variation.

We will look at each of these three main aims in turn, under the titles:

This article first appeared in Modern English Teacher Volume 27 Issue 1 (Jan 2018).

The What

What it is

The Hexagon Vowel Chart is a representation of the English vowel system. Each phoneme is represented with an International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) symbol plus a word containing the phoneme in a typical spelling, underlined. The vowel phonemes are placed in hexagon-shaped cells in a honeycomb in a way which highlights certain relationships amongst them.

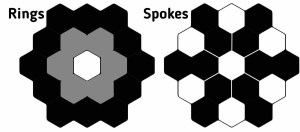

Rings There are patterns of concentric rings, with longer vowels on the outer ring, shorter vowels on the inner ring and the schwa in the centre. The longer vowels in the outer ring include the long vowels at each of the six corners and the diphthongs in the middle of each of the six sides.

Spokes The figure contains six radiating lines, or spokes. The vowels in within each spoke are roughly similar, but with a short one nearer the centre and a longer one further from the centre – for example, the foot vowel = short and the boot vowel = long.

Top-Bottom The long and short vowels are placed on the honeycomb as a whole roughly according to how they are articulated. Phonemes placed near the top such as /i:/ are produced with the jaw more closed while the phonemes further down such as /a:/ are produced with the jaw more open.

Left-Right Long and short vowels placed further to the left are produced with the mouth wider and the tongue more forward, phonemes placed further to the left (except for the duck and bird vowels) are produced with the lips rounder and the tongue further back. The duck and bird vowels are produced with the mouth in a more relaxed, neutral position.

What it is for

The Bigger Picture Introducing his well-known phonemic chart, Adrian Underhill suggests that, ‘The chart is not a list to learn, but a map representing pronunciation territory to explore’ (Underhill, 2005), and the same goes for the Hexagon Vowel Chart too, although the map is organised in a different way. While learners could just get by working on vowels one by one in piecemeal fashion as problems arise, a map can help them see the bigger picture – how the phonemes relate to one another in the system as a whole.

Motivation There is also a motivational angle which Underhill points out. If you don’t have the map, you don’t know how much you have explored and how much you still have left to explore, making the learning task feel potentially infinite and insurmountable. It is motivating to know that the territory has limits.

The How

In this section, we will look at how to present the hexagon vowel chart in class. First of all, we will look at possible ways of breaking down the whole system into bite- sized chunks suitable to be presented in one session. We will then look at ideas for classroom procedures for working with these chunks.

How to break the vowel chart into bite-sized chunks

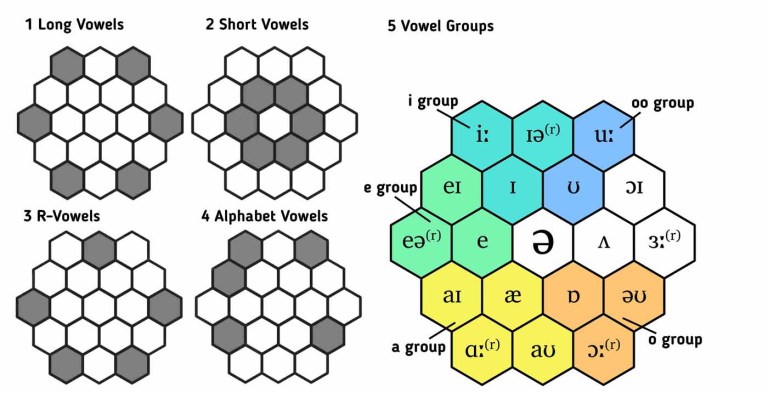

The figure below shows possible groupings of phonemes in the hexagon vowel chart which may form the focus of single classroom pronunciation sessions. We will look at these five in turn.

1. Long Vowels

We saw above that the long vowels occupy the six corners of the chart. These are a good set to start presenting the chart to the class with. This is because these long vowels, unlike those on the rest of the chart, can be made as long as you like. Consequently, when you model them for the learners, they get to hear a good long sample, with plenty of time to savour the sound and observe your mouth positions as you create them. (Bear in mind that in this chart, the hair vowel is regarded as a long vowel rather than a diphthong (see Cruttenden, 2014). Also note that long and short are simplified terms, and these vowels are not necessarily longer or shorter in all accents or contexts).

2. Short Vowels

In the inner circle of the Hexagon Vowel Chart are the short vowels. Unlike the long vowels, these cannot be made long without losing their character. For this reason, they are better demonstrated by saying the short sound repeatedly. For example, you would say the foot vowel repeatedly, like the sound of a monkey, rather than long and drawn out.

3. R-Vowels

Some phonemes on the chart have (r) beside them. This indicates that these vowels most commonly occur before a letter ‘r’ in the spelling. This ‘r’ may or may not be pronounced, depending on accent, but either way, the vowel is influenced by it. Notice that these r-vowels all occur in the outer circle. This is no coincidence, because the effect of the ‘r’ is often to lengthen the vowel.

4. Alphabet vowels

These are the five vowel letters of English, A, E, I, O and U, as they are pronounced in the alphabet. Three of these are diphthongs, the other two are long vowels. Remember that the alphabet pronunciation for U also has a /j/ before it – /ju:/.

5. Vowel Groups

The vowel phonemes which are located next to each other on the chart can also be presented in smaller groups, as shown in part 5 of Figure 3. For example, the ‘e’ group includes the vowel phonemes in face, hair and leg. These are similar, but contrasting in a number of ways. Note that the colours on the vowel hexagon chart are suggestive of these groupings.

There is an advantage in presenting vowels in groups like this rather than traditional minimal pairs. A minimal pair focuses on one distinction, and for those learners who do not have a problem with that distinction, there isn’t much to learn. Vowel groups contain more than one distinction, and there is more likely to be something of relevance for everybody in the class.

How to work with the chart in class

Morph drills Point at two phonemes, for example the teeth and boot vowels and get the class to say them – Eeeeeee! Ooooooo! Then point at one and move the finger to the other and get the class to say it, morphing from one phoneme to the other – Eeeeeeeoooooo! This works particularly well for the long vowels, and allows learners to compare one with another.

Articulation experiments Repeat the morph drill described above, but this time ask the class to focus on what changes in their mouth position as they make the change.

For example, ask them to morph from the teeth vowel to the arm vowel with their finger on their nose and their thumb on their chin. They will notice that the finger and thumb move apart – proving that the jaw drops down during the change from one vowel to the other.

Vowel mnemonics Suggest, or get the class to suggest, fun mnemonics for the sounds. For example, the boot vowel could be called ‘the nice surprise sound’ because people often say it to express surprise. The foot vowel could be called ‘the monkey vowel’, as mentioned above.

The vowel orchestra This activity is good as a review, when all of the phonemes on the chart have already been presented to the class. The class is the orchestra and you or one of the students can be the conductor. The conductor points at the phonemes and the orchestra calls them out, continuing the long vowels or repeating the other vowels for as long as the conductor keeps his or her finger on that symbol.

Spelling patterns Choose one of the vowel groups mentioned above and give or elicit a large number of examples of words containing those vowels. Then ask the class to identify the different ways in which that phoneme may be spelt. Elicit which spelling patterns are common and which are unusual. For example, for the teeth vowel, ‘ee’ and ‘ea’ are common while ‘ie’ (as in piece) is unusual.

See PronPack 1: Pronunciation Workouts (Hancock, 2017) for more detail on the activities above.

The Why

In pronunciation teaching, we need to keep in mind the why question – why are we teaching it and why do the class need to learn it? Bearing in mind the role of English as an international lingua franca, it is probably fair to assume that the majority of learners need to be intelligible, rather than needing to sound like native speakers. See for example Robin Walker’s series on English as a Lingua Franca in Modern English Teacher (Walker, 2015).

Why is the map flexible?

If we accept accent variation as the norm rather than the exception, then our vowel chart needs to be flexible enough to accommodate that variation, and the Hexagon Vowel Chart attempts to do just that. Hence, for example, the optional (r) next to some of the symbols. This enables the chart to work for accents where that ‘r’ is pronounced, such as American, and those where it isn’t, such as English.

Phonemic, not phonetic In order to be accent-flexible in using the chart, it is important to remember that the IPA symbols in it are phonemic rather than phonetic. A phonetic symbol represents a precise sound. A phonemic symbol is less specific – for example, /e/ can be defined as the vowel sound in leg, no matter what the speaker’s accent.

Optional Schwa The position of the schwa at the centre of the chart is not intended to suggest importance, but rather that it is exceptional. It is a reduced sound which occurs only in unstressed syllables. Trying to compare it to other phonemes such as the vowel sound in duck for example is a recipe for confusion. In fact, it is probably better not viewed as a phoneme at all, but an unstressed variant, or allophone, of one of the other vowel phonemes – most can be reduced to schwa. For example, in the name Canada, the second and third vowels are often pronounced as schwa, and in this instance the schwa would be an allophone of the hand vowel. Learners will need to understand the schwa receptively, but for production it is optional – not essential for intelligibility.

Why put vowels on the map?

It is easier to teach consonants than vowels. With consonants, there are fixed points where contact is made in the mouth, for example between the tongue and the teeth. It is more difficult to navigate the vowel sounds. With no fixed points, their position can only be explained relative to one another in a system. It’s useful for learners to have an overview of this system, and that’s the great advantage of putting vowels on the map.

References

- Cruttenden A (2014) Gimson’s Pronunciation of English (8th Edition), Routledge, Oxford

- Hancock M (2017) PronPack 1: Pronunciation Workouts, Hancock McDonald ELT, Chester

- Underhill A (2005) Sound Foundations: Learning and Teaching Pronunciation (2nd Edition) Macmillan, London

- Walker R (2015) The globalization of English: teaching the pronunciation of ELF, Modern English Teacher, 24.4, 2015

The chart can be freely downloaded in high resolution from here.

This article first appeared in Modern English Teacher Volume 27 Issue 1 (Jan 2018)