Annie has worked in ELT with great passion for the last 40 years, but her teaching career began even before that, in her home town of Liverpool. She qualified there as a teacher in 1976 and went on to teach history in secondary schools. Straight away, she understood the importance of motivation, and how to make the content of her classes relevant for learners, especially for those whose backgrounds were not exactly privileged and encouraging of learning. This desire to reach out to the learner, to teach the person rather than the course, endured throughout her career.

If Annie was a popular, well-loved teacher, it was because of her tireless effort to understand her learners, and put herself in their shoes. In fact, later on in her career, motivation was to become one of Annie’s particular interests – a topic about which she went on to write many articles and conference presentations. It was also a key aspect of a series of coursebooks that she and I wrote for Oxford University Press – English Result. In that book, each lesson was conceived as a journey from How to (the objective) to Can do (the outcome). Concern for motivation informed every step of this journey.

Annie’s belief in learner training and the motivating effect of ‘can do’ outcomes naturally lead her to take a great deal of interest in the work of the Council of Europe, and the Common European Framework of Reference. Few teachers could match Annie’s painstaking patience in matching classroom practice to the lists of competencies in the CEFR documents. Her determination to get it right was based on a passion for fairness, and this fed into her work on testing and assessment, which formed to bulk of her most recent work at the University of Chester. Annie was not one to give in to the temptations of an easy life, even when under pressure to do so. ‘Sticking with it’ was a key aspect of her professional personality; she could be trusted to do things properly.

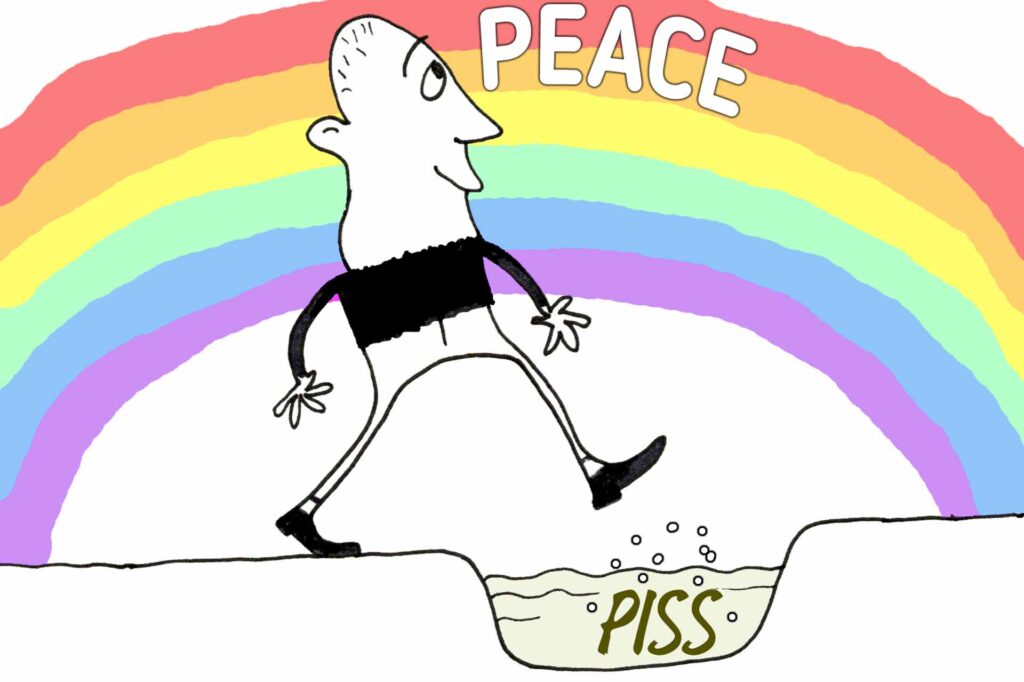

Annie was always keen to push ahead with continuous professional development, constantly signing up for courses and conferences, and perhaps the biggest commitment of all: a Masters degree in Teaching English. This she did with Aston University, but at a distance, alongside a group of like-minded colleagues in Madrid. Among the special interests which emerged out of that course were English for Specific Purposes, Course and Syllabus Design, and Skills, especially writing and listening. With regard to this last item, Annie was convinced that there had to be a place for authentic audio material; so much of what passed for listening work at that time was based on artificial, ‘cleaned up’ audio material created by publishers based on scripted dialogue. Everything we learned at Aston about discourse and conversation analysis indicated that the challenge of listening is in the more unexpected, unnoticed aspects of speech; the kinds of things the script writers rarely included. This is what motivated Annie and I to embark on the project of writing a book of materials for authentic listening (Authentic Listening Resource Pack, from Delta Publishing).

Aside from pushing ahead with her own professional development, Annie was also committed to helping others do the same, and hence the hours and years she devoted to voluntary work for TESOL Spain. In her role as convention coordinator, she was able to give many ELT professionals their first opportunity to present at a major conference – perhaps you are one of them yourself? – and this is something many people have mentioned in their tributes upon learning of Annie’s death. Annie would later go on to become president of TESOL Spain (from 2000 to 2002), and then Liaison Officer and Honorary Advisor.

From what I have written above, readers may have the impression of a dedicated worker, very serious about her career, but that would be to miss another aspect of her professional presence: her lively and fun-loving character. This was well reflected in one of her earliest achievements in her ELT trajectory, namely her key role in instituting an annual pantomime and the Cultura Inglesa chain of language schools in Rio, Brazil. Like the carnival, planning for these events started almost immediately after the previous one had finished, and involved bringing together vast teams of willing volunteers in hours of work and often hilarious fun.

Now, Annie McDonald is no longer with us, but long may her memory live on amongst the many people in the world of English Language Teaching, whose trajectory has crossed with hers, in one way or another. She has enriched us all.